David Henri Gallandat’s Necessary Instructions for Slave Traders (1769)

When we began this series of blogs, the intention was to examine sources testifying to the role of medicine in the slave trade. In the opening post, I wrote that such links could often be indirect, as for example in the case of practitioners like Samuel Brun who travelled down the West Coast of Africa before the formation of formal slaving companies. The source at the heart of this post is, more or less, the opposite. It reminds us that sometimes medical involvement in the slave trade was not only direct, it was formally addressed, carefully crafted, and disseminated as a conceptual basis for professional and social expertise.

Images: Susanne Caron, Portrait of David Henry Gallandat, 1759. Pastel, 550 x 448 mm (frame). Middelburg, Zeeuws Museum, kzgw Collection, inv. no. g1599.

From the seventeenth century onwards a number of slave surgeons from across Europe wrote and published texts, which reflected on their formal, professional intervention in the slave trade. These include well-known works by British surgeons John Atkins and Alexander Falconbridge. They also include texts by surgeons who worked in other European slave companies, such as the former chief surgeon for the Dutch West India Company, Louis Rouppe’s Diseases of Seafarers, or the German Adolph Friedrich Löffler’s “Begriff vom Sklavenhandel”. One such text, and the subject of this post, was “Necessary Instructions for the Slave Traders” authored by David Henri Gallandat (1732-1782), which appeared in Middelburg in 1769. Gallandat, a Swiss surgeon who was by the time of the text’s appearance a university lecturer and an aspiring mover and shaker in the local learned academy, wrote for a primarily Dutch audience. The original text is now available online, and excerpts have also been translated by the archival project On Board the Unity by the Zeeland Archives. Necessary Instructions was a short text, only some forty-two pages in total. Gallandat was neither a polemicist, nor an abolitionist. His text covered justifications for the slave trade as well as (mild) criticisms of its excesses, but it was entirely uninterested in making an intervention in ongoing abolitionist debates. Rather, it was intended for an extremely local audience, and took as its premise a celebration of the central role of Vlissingen in the slave trade. As Gallandat boasted, “Amongst all the sea ports of our Netherlands there is none where the merchants apply themselves more to outfit ships for the slave trade than in VLISSINGEN”. He quantified this advantage numerically, of a total of 6300 slaves trafficked in the same two years, he boasted that they included ‘3100 by the Vlissingers alone”.

To this success Gallandat attributed the role of medical expertise: “The success of the slave trade depends very much on the good procedures and skills of the surgeons”. To that end, the text attempted to provide a comprehensive guide to the role of the surgeon on board the slave ship.

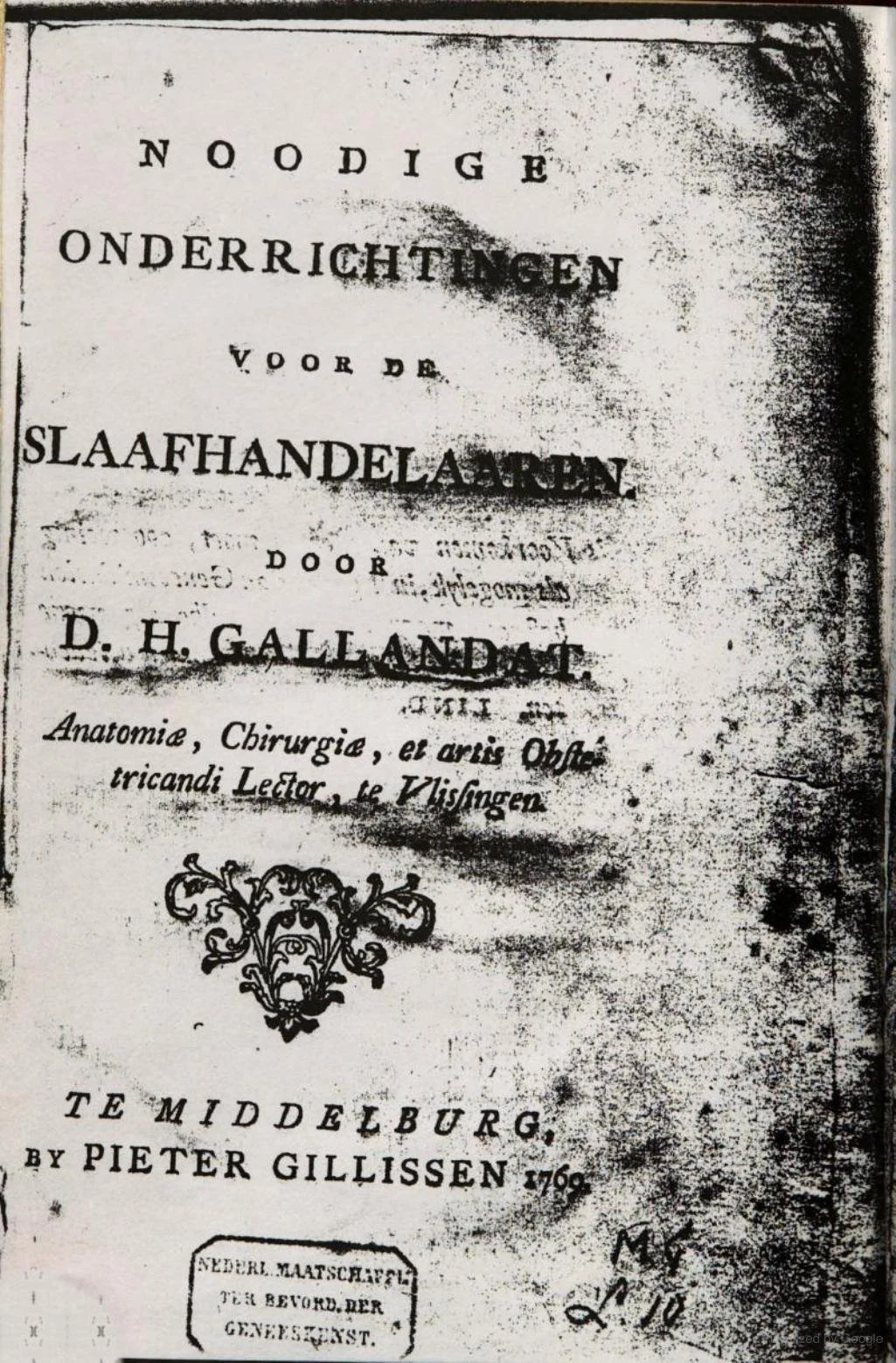

Images: Frontispiece, David Henri Gallandat, Noodige onderrichtingen voor de slaafhandelaaren, Middelburg, 1769.

This included first and foremost overseeing the selection of enslaved prisoners, which should be “young, strong, unmarred, and healthy”. There were commercial reasons for this, such as the price such individuals would fetch on the other side of the middle passage, but there were also medical reasons, which more or less reduced to the difficulty in healing sick enslaved people on board ship, and to preventing contagion in the case of illnesses on board.

The site of the Middle Passage as a laboratory for suffering, a site of abjection, and a liminal stage in the (contested) process of social death, has been amply studied by historians including Stephanie Smallwood, Sowande Mustakeem and Elise Mitchell. Gallandat explained the difficulty of keeping slaves alive by virtue of these conditions, and while it is not, I think, necessary to lay them out here again, it is worth noting that the text confirms these conditions with chillingly clinical indifference, reminding his readers that, given such circumstances, “one can easily understand that it is very difficult to carry a cargo of slaves in good physical shape to America”. Here, the expertise of the slave surgeon is based on and amplified by the conditions of middle passage. It is indeed far from a virtuosic portrayal of medicine that Gallandat offers. He is clear that: “the measures which are put in place to prevent diseases have a more certain result than those which are used to heal the sick”, and he enumerates these in terms of better amounts of space, more circulation of air, improved practices of hygiene and cleanliness, a more well rounded and plentiful diet, and the provision of space to exercise.

The enumeration of the bad conditions aboard ship and the recommendation for improvements take up the bulk of Gallandat’s text – and it is worth considering the kinds of claims to expertise and the rhetoric this implied. Where prevention rather than curing is the main duty and professional activity of a role tied to medicine, what kind of expertise are we really being offered? Gallandat does not sidestep the role of curative medicine altogether. When called to treat enslaved people, the medical practitioner must attempt to “treat the sick slaves well, and to employ everything within the ship which could lead to its healing”. There is no need in this text however to go into details about treating diseases, since such detail can be found in texts by “TITZING”, “LIND” “P.DE WIND” , ROUPPE, SE. DE MONCHY. Gallandat’s references here to existing literature act as helpful summary to the state of the field and suggest that not only were texts on slave medicine being written by practitioners, they were also appearing in conversation with each other. Where Gallandat does make some specific observations about medical practice, their significance rests in the unusually assertive exhortation he offers to study and research indigenous practices and materia medica, particularly Goeyave roots, Cortex simarouba and Emphysema artisiciale.

One of the things that jumps out of Gallandat’s text is the idiosyncratic balance he attempts to strike between enumerating his areas of expertise on the hand, and the often oblique language with which he describes its day-to-day affects. In a section of his text which has previously gone unremarked, he alluded to, for example, the specifically gendered nature of slavery and violence:“it is therefore not surprising that such a slave, when he finds himself on board to be sold, and to say his last farewell to his land, that he is sometimes seized with violent emotion. This however is more common among the women than with the men, due to reasons known to all physicians and surgeons, and therefore unnecessary to report here.”

What are these reasons, which are “known to all physicians and surgeons”? What did medical expertise mean if it subsumed into itself these details, even while proclaiming itself an authority to investors, literati, and university fellows? How might we think of Gallandat’s silence here defining a body of knowledge at the heart of growing profession? Further research might answer these questions, while further thinking can perhaps furnish the language to position these silences in the wake of the ‘morbid traces’ of the middle passage. Research could perhaps also clarify or draw out the suggestive connections between Gallandat’s surgical interests (obstetrics, in particular caesarean sections,) and his experiences on slave ships. Here, I wish only to make the point that running through this text is a formulation which precisely locates the slave surgeon as central and necessary to the slave trade, while suggesting a carefully crafted silence about the constitution of their craft. A manual such as Gallandat’s can thus be interpreted as a capstone to the process our project addresses. By laying out the specialised expertise of the slave surgeon in this way, Gallandat claimed not just the centrality of medicine to the slave trade, but – somewhat inadvertently – laid out the centrality of the slave trade to developing specific forms of medical practice.

Hannah Murphy, Medicine and the Making of Race: Principal Investigator